Over time, the journeymen who had been trained in companies such as San Pedro in Elgoibar, La Euscalduna in Soraluze and Orbea in Eibar, among others, set up small auxiliary workshops, dedicated to the manufacture of tools, machining of spare parts and repair of machine tools.

Due to a natural course of events, some of these Basque companies began to manufacture machine tools at the end of the 19th century, approximately 75 years after the first English manufacturers. Our history as machine tool manufacturers begins at the end of the 19th century.

The arms industry experienced its last great heyday during World War I (1914 – 1918). Then comes the decline: it’s do or die. The ensuing metamorphosis is dazzling. The existing companies abandoned the manufacture of weapons and converted to manufacturers of machine tools (Ciaran and Estarta, Cruz Ochoa, Orbea), bicycles (B.H., Orbea, G.A.C.), sewing machines (Alfa, Sigma), etc. as if they had been doing it

all their lives. And, in a way, this was the case; the Basques had undergone numerous transformations over the centuries, and this was simply another one.

Of course, this diversification would not have been possible without the experience gained during the county’s dazzling and successful history of gunmaking, because gunmaking requires above all knowledge and precision. Anyone capable of making a weapon is capable of making anything.

Ciaran and Estarta from Elgoibar

José León Ciaran (1876-1948)

JLC (José Leon Ciaran) pillar drill.

He was born in the Mizpillibar farmhouse in Alzola, a neighbourhood of Elgoibar. Afterhis initial studies in Alzola, he started as an apprentice gunsmith in Markina in 1890. He fought in the Cuban War, where he met Juan Caballero, a lawyer from San Sebastian.

On his return from the war he went back to work in Markina, until he set up his own workshop in San Francisco Street in Elgoibar in 1898. His friend, Juan Caballero, accompanied him to Belgium, where he obtained the plans to manufacture drills. He started the business with the help of his partners, doctor Tomás Zubizarreta and Juanjo Goyogana.

Eulogio Estarta (1891-1955)

He came from a working-class family without enough resources to provide him with a formal education. At the age of twelve, he lost his father and, being the eldest, he was forced to become an apprentice at Fundiciones San Pedro in Elgoibar to help the family out.

In San Pedro he completed an apprenticeship as a mechanical fitter. Estarta was a very responsible young man, taking on the sacrifice of training outside working hours, attending evening classes at the School of Arts and Crafts in Elgoibar, where he attracted the attention of his teachers because of his great aptitude for drawing and mechanics.

In an effort to improve his skills, Estarta moved to Bilbao, where, for some time, he

alternated his work in a mechanical workshop with his studies in drawing and

mechanics. At the age of 23, he returned to Elgoibar, joining forces with Ciaran.

On 21 April 1914, the company Ciarán y Estarta was set up by José León Ciarán

Arrillaga and Eulogio Estarta Landa. The new workshop started in the repair and

construction of machines and devices for the arms industry, with a special focus on the manufacture of machine tools.

The capital available to develop their business was soon insufficient, which is why José León Ciaran and Eulogio Estarta brought in Teodoro Ecenarro from Elgoibar as a partner. On 21 September 1915, a regular partnership called Ciaran, Estarta y Cía. was set up, dedicated to the construction of machinery, with registered offices in Elgoibar, Calle San Francisco, house with no number, owned by Juan Irusta.

Estarta and Ecenarro from Elgoibar

On 18 September 1920, the company Ciaran, Estarta y Cía. was partially terminated, becoming Estarta y Ecenarro. José León Ciaran, ceases to belong to the company and, as from the date of the signing of the deeds, the company trading under the name of Ciaran, Estarta y Cía. changed its name to Estarta y Ecenarro. They paid off the debts incurred and a few years later it was a profitable and consolidated company.

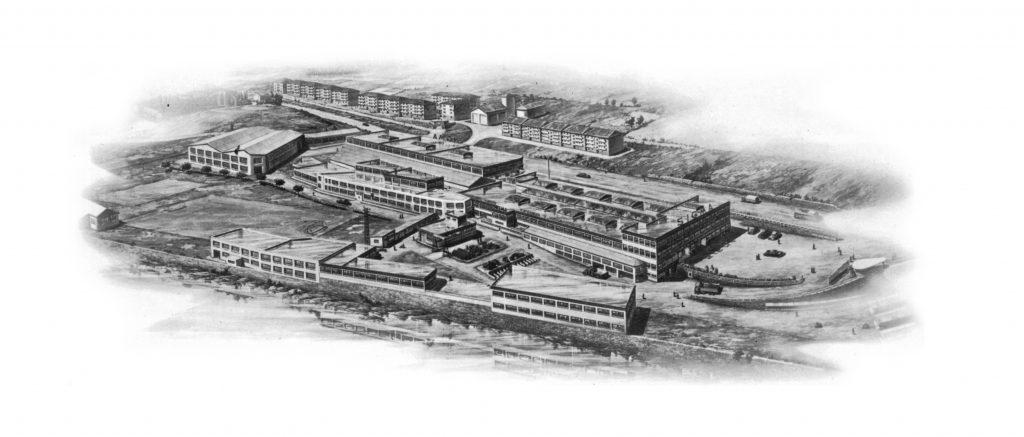

At the time of the Civil War (1936-1939), Estarta y Ecenarro, located in the street Santa Ana, was dedicated, like many other workshops in the area, to the manufacture of weapons. After the war, with the aim of starting to manufacture sewing machines, they acquired land next to the Olaso cemetery, where they built new workshops to combine the manufacture of machine tools and Sigma sewing machines.

In the new factory, to meet the demand of pillar and bench type drilling machines after the Civil War, the production and range gradually increased. It successively manufactured various types of eccentric, gooseneck and double upright presses.

Around 1948, the company built the first hydraulic copying lathe, based on a Swiss model of the company Dubied. Estarta y Ecenarro was also the first manufacturer of centreless grinding machines, launching a small model at first and completing the range in subsequent years.

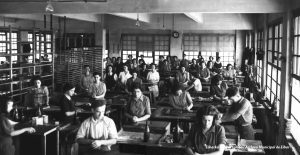

The participation of women in the manufacture of sewing machines was decisive in the production, assembly and threading of these machines. In general, women, having smaller and thinner hands, were more capable of handling and assembling small parts of these products, which required skill rather than physical strength. Of course, the money earned was meant to support the household economy, but it also meant women gained a certain independence. However, the incorporation of women on the labour market and the greater supply of ready-made clothing meant that housewives stopped sewing at home, resulting in a sharp fall in the sale of sewing machines.

Moreover, with Spain's entry to the European Union, Estarta y Ecenarro (SIGMA) failed to adapt to the new situation. Basque companies realised that they were far from being competitive in international markets and that they were almost a generation behind in terms of technological evolution.

In 1990 Estarta y Ecenarro launched a new sewing machine, the “Sigma Book”, which was a failure. This marked the beginning of the end of Estarta y Ecenarro and in 1995 the company went into receivership.